Poetry’s Role in Building Confidence for Teens and Young Adults | Chinaza James-Ibe & Russell Ndoboke

Poetry

Pablo Neruda

And it was at that age… Poetry arrived

in search of me. I don't know; I don't know where

It came from winter or a river.

I don't know how or when,

No, they were not voices; they were not

words, nor silence,

but from a street I was summoned,

from the branches of night,

abruptly from the others,

among violent fires

or returning alone,

there I was without a face

and it touched me…

It’s hard to imagine a better way to begin. In this poem, Pablo Neruda describes poetry as a force that finds him, awakens him, and carries him into the universe of language and feeling. It arrives like a fever, like fire, like forgotten wings.

And for so many teens and young adults, it arrives just the same—unexpected, unexplainable, and life-changing.

There are few things as quietly powerful as a teenager finding their voice—and few tools as potent in that discovery as poetry.

In a world that often rushes young people into silence or self-doubt, poetry gives them permission to speak, to feel, and to be complex. It’s one of the rare art forms that doesn’t require permission or precision—only presence. A blank page doesn’t ask for credentials; it waits patiently for truth. And when a young person fills that page with their pain, their joy, and their contradictions, they begin to see themselves more clearly.

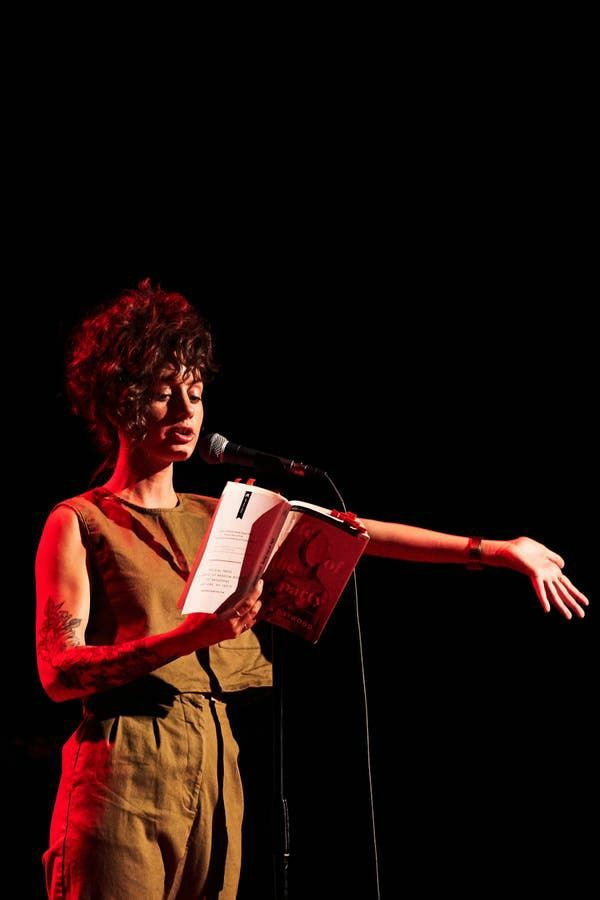

Confidence doesn’t arrive all at once. It grows slowly, line by line. It takes shape in the moment a shy teen reads their poem aloud for the first time, hands shaking, voice trembling. Or when someone says, “That’s exactly how I feel too.” It builds in workshops and late-night scribbles, in journals tucked under beds and open mics where nerves meet applause. It deepens when they realize they can hold both questions and answers in the same stanza—and that their truth has weight.

In this article, we explore how poetry serves as both mirror and compass for teens and young adults. First, we reflect on the emotional and developmental impact of poetry on youth confidence. Then, we look into poets who began writing in their teenage years—those who let poetry touch them, like Neruda, and learned to make meaning from the flame.

For many, poetry becomes more than a pastime. It becomes a practice of self-assertion, a ritual of emotional honesty, and a rehearsal for speaking up in other parts of life. It teaches rhythm—not just of language, but of the heart. It teaches restraint and release. It teaches that even the quietest voices can echo.

This is something Amanda Gorman knows well. Before she ever stood at a presidential podium, she was a girl with a notebook, a speech impediment, and a deep sense that her voice mattered—even if it trembled. Through poetry, she found not only fluency but also power. Writing gave her something solid to hold, something certain in a world that often felt slippery. She has said that poetry helped her push through fear—and what is confidence, really, if not the willingness to speak even while afraid?

And she is not alone. Across the world, other young poets are writing themselves into being. In Nigeria, Victory Ashaka discovered poetry at twelve, after winning a local competition. He kept writing—about the land, about identity, about climate—and that persistence led him to the United Nations, to TEDx stages, and to classrooms where he now mentors others. But his journey began the way so many do: with a line scribbled in the margin of a school notebook. A line that said, "I feel this." A line that dared to ask, do you?

In Côte d’Ivoire, Noferima Fofana carries the music of her ancestors into her poems. Writing in Koyaga, her native language, she speaks of memory, womanhood, and the changing rhythms of a continent. She won the Slam World Cup in Paris not by bending herself into another’s shape, but by speaking with the full force of her own. Her poems are not just performances—they are offerings, stitched with pride, grief, and the wisdom of many mouths.

And in the diaspora, Oyewumi Oyeniyi—Nigerian by blood, Philadelphian by birth—writes from the in-between. At 17, she was named the city’s Youth Poet Laureate, and her work grapples with what it means to grow up in a body shaped by two cultures, two expectations, and two languages of becoming. Her poetry speaks to the tension of dislocation but also to the strength it forges: “My existence,” she once wrote, “is the poem they tried to erase.” In saying so, she made herself unforgettable.

From Nigeria, Chinecherem Enujioke, a young poet and honorable mention of the 2024 ZODML Poetry Prize, comments on her initial feelings towards poetry. Having been introduced to the prolix verses of the Victorian era in school, Chinecherem felt estranged and convinced that most, if not all, readers of poetry were pretentious. However, she found her voice when she came in contact with contemporary poetry—poetry in a ‘language’ she could understand, a language she could feel in.

Chinecherem is both a page and performance poet, and while these two forms might suggest a disparity in confidence levels, she believes that expression is not—and never has been—a binary concept. Both forms of poetry work towards the challenging of norms and the breaking of boundaries, she says, citing the legacy of poets such as Louise Glück, Warsan Shire, Zaynab Bobi, Pacella Chukwuma Eke, and Fatihah Quadri Eniola.

In Nigeria, shame is too often peddled as a virtue—and shaming itself weaponized as a tool of oppression. By holding things up to the light and churning out stories from honest places, poetry is rewriting that narrative, whether people recognize it or not.

“For me, poetry is a means of speaking up—of speaking against my oppression, and the oppression of other people.” – Chinecherem Enujioke

For Bernard Nweke, winner of the 2024 ZODML Poetry Prize, poetry began as a medium of expressing wonder—a sincere awe of life—and subsequently blossomed into a language through which he could explore the political landscape of the country and express his views without fear. Poetry gave him a voice.

These poets—Chinecherem, Bernard, Ashaka, Fofana, and Oyeniyi—represent a rising tide in West African youth culture, where poetry slams are packed with eager ears and open hearts. Poetry collections and online publications are shared and read like scripture. In Lagos, Accra, Bamako, and Abidjan, young people gather not just to recite but to witness. To say, "This is how I survived today." This is how I loved, feared, and laughed. This is what I carry. The slam becomes a sanctuary, the page an altar, and the mic a mirror. Each voice sharpens another.

Even beyond the stage, poetry lives in the quiet places—in WhatsApp groups and under-the-bed journals, in morning commutes and evening scrolls. It lives where a teenager writes in secret, unsure of whether the words make sense but certain that they mean something. It lives where a teacher says, “Try again.” Where a friend says, “Read that part out loud.” Where a stranger in the crowd says, “I felt that too.”

And slowly, confidence grows. Not always loudly. Not always quickly. But steadily—like water under stone. It grows in the realization that someone else sees themselves in your words. That your voice, however hesitant, has reached another shore. That poetry is not about being perfect—it’s about being present.

Poetry doesn’t offer all the answers. What it offers is a place to ask the questions out loud. To sit with contradictions. To carry both heartbreak and hope in the same breath. To feel and be felt in return.

And maybe that’s the most powerful part: poetry doesn’t demand that you be fearless. It asks only that you be honest. That you show up. That you speak in your own language, in your own rhythm, from your own fire. And when you do—when a young person dares to say, “This is me”—the universe does not look away.

It leans in.